Can thinking about our moral obligations actually make us less compassionate to others?

That may sound strange. After all, isn’t morality a reason why we treat others well? But the question reminds me of a famous study in economics.

In 2000, researchers following daycare centers in Israel found that after they imposed a fine for picking up children late from daycare, late pickups actually increased by 40%.1

The key insight is that financial motivations can crowd out other more intrinsic motivations. The inclusion of a financial penalty for something that was originally free prompted parents not to ask, “Is this the right thing to do?”, but rather, “Is this worth the money?” It replaced a social norm with a market transaction.

I’ve been thinking about how this “crowding out” phenomenon can apply to other motivations. Maybe focusing on moral obligation (and a desire to be a good person) can crowd out our intrinsic desires to actually do good things for others.

Readers of this blog may know that I’ve been kind of obsessed recently with the idea of moral obligation. I think a lot about what it means to “do the right thing” and to “be a good person.”

At first glance, these can seem like good motivations! Isn’t it good for people to be good people and do the right thing? I think the answer to that is broadly yes. But I think an excessive focus on one’s moral standing can actually be counterproductive.

I’ve been in a bit of a rut recently. I’m currently job searching and thinking a lot about what I want to do next in my life — and what, more broadly, I’d like my life to be about. That’s often left me with a tension between what I want to do and what I should do. (Get a comfortable, stable job? Nonprofit work? Or startup social impact venture? Or…?) And so when my want and my should aren’t perfectly aligned, I have felt really guilty and bad about myself — a sense that I’m failing or not doing the right thing. It’s more apparent to me now that all that rut thinking has drained my energy from other things I care about.

I recently came back from a 10 day silent meditation retreat. It was quite intense. The Vipassana retreats were started by a Burmese businessman in the 1970s who claims to have rediscovered the pure form of meditation originally practiced by The Buddha thousands of years ago. The whole retreat (which in my case included ~80 people divided in half by gender) is offered with zero communication with other participants: no eye contact, gesturing, or spoken word allowed.

To start the retreat, we take several ethical vows. Do not kill, do not lie or steal, etc. For a while, I wondered what the basis for these vows were. After all, this was a meditation course to bring inner peace — not a moral philosophy class! And then at the end, they revealed the answer.

The purpose of the ethical vows was to keep you from doing anything that would make you feel guilty and therefore prevent you from getting out of your head.

The pathway to feeling inner peace and clarity, say many Buddhist meditative traditions, is to lessen the ways in which we obsess about ourselves — to quiet the inner voice that can take up so much of our time and attention. And one of the ways we can get caught up thinking about ourselves is when we feel guilty about doing harm to others.

This Vipassana version of Buddhist meditation was not designed to cultivate morally good human beings. But that seems, in their worldview, to be an invaluable side effect. By sitting together in over 100 hours of silence (10.5 hours / day over 10 days), participants learn to let go of the habits of thought that on a day-to-day basis that can entangle us in our own heads. And when that happens, more space is created for compassion for others — not as a goal, but something that starts to arise naturally.

This approach seems to work for them. There are over 250 Dhamma Vipassana centers across 94 countries. They’ve hosted millions of attendees for intensive retreats — each is completely free and funded entirely through voluntary donations.

And so now, I wonder how much all my obsessing over morality has actually been counter-productive. Asking “Am I a good person?” can keep us overly concerned with our self-image, rather than actually doing good things for others.

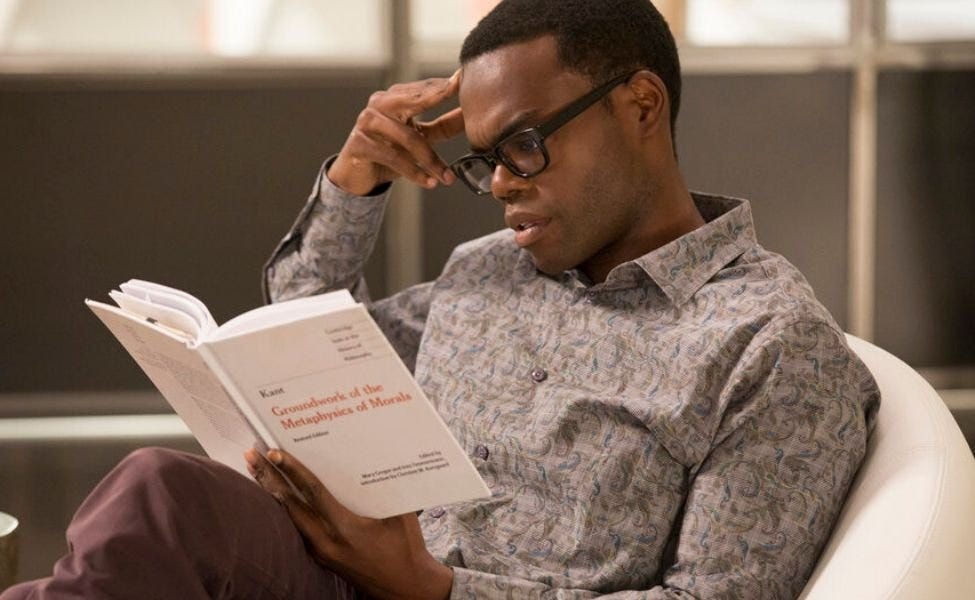

That’s roughly aligned with the worldview of The Good Place, a widely popular TV show about moral philosophy. (It’s so good!) It was created with UCLA moral philosophy professors — and surprising to me, their thesis is that you cannot try to be a good person. If your motivation is to “be good”, then you are actually pursuing self-interest around who you want to be rather than doing things selflessly.

When I first heard that thesis several years ago, I basically tuned out. It seemed absurd to me. How can it be wrong to want to be a good person? But as I have experienced more of the world, I’m really starting to resonate with their point.

One benefit of my meditation practice has been to calm the voice inside of me that can obsess over whether I am good. And in that calmness, I am noticing how compassion naturally flows, without the effort and overthinking that has usually come with my moral pondering.

Ancient traditions like Buddhism have shown that when we let go of all the silly complexities that our societies create — from our definitions of social status to our laws that order who does and does not have a right to the fruits of this earth — we as humans are left with a natural desire to be kind.

Moral reasoning can point us in the right directions and help us identify blind spots in what we currently see as urgent or morally good. But perhaps it’s not something we need to motivate us to be good. It seems to me that with the right room to breathe, that’s a desire that lies within all of us already.

The fine was quite small — approximately three US dollars in today’s money. Another takeaway is that financial penalties do work; they just need to be high enough to actually disincentivize the intended behavior. It was cheaper for the parents to pay the low late pickup than for an extra hour of daycare. But it is remarkable that even though it was originally free to pick up children late, an added financial penalty only served to increase the undesired behavior. The study, which has been referenced in thousands of academic papers and popular science books as Freakonomics, does seem to reflect broader truths about intrinsic human desires and social norms.

How does releasing self-concern (ex: asking whether I’m a good person) create natural space for compassion?

An answer: humans are naturally empathetic. We each know what it is like to suffer, and that we don’t want it. So when we release our attachment to our own suffering, we more freely notice the suffering of others. And because we have lessened our sense of self, we start to feel others’ suffering **as if it were our own.** This seems to be the core of empathy. And luckily, there are specific practices we can do to cultivate that. (And inspiringly to me, these practices work because all they do is uncover who we as a species — and who knows, maybe all species — naturally are.)